How NOT to teach mathematics

I am always saddened me when smart, educated, accomplished people say “I hate math” or “I’m not good at math” when that is demonstrably false. I was confused by hatred of something which is so integral to almost any intellectual effort. I eventually discovered (by exploring) that what these people think of as “math” was not the beautiful realization of perfect ideals which I had learned. The hated “math” was the seemingly arbitrary, boring, dull, rote process of memorizing abstract concepts and how to manipulate them without any connection to a grander context. This is a failure of teaching. The vibrant discovery of mathematics is beaten out of students with rote multiplication tables and strict adherence to notation over understanding. It’s tantamount to showing an apprentice carpenter how to use a hammer and nails to join two pieces of wood but never making space to build anything. No wonder people “hate math”.

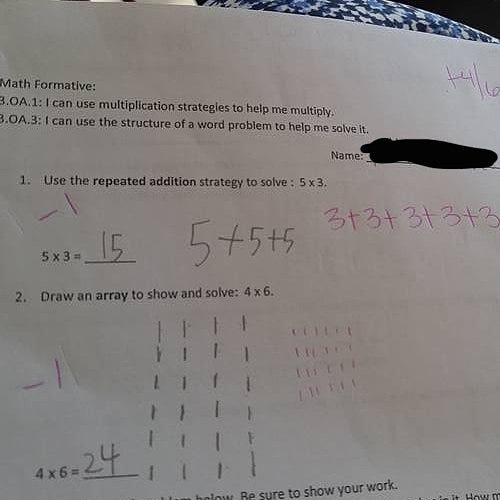

A perfect example of why people hate math is demonstrated by an article which showed up in my RSS this morning. Why 5 x 3 = 5 + 5 + 5 Was Marked Wrong, a defense of the teacher who graded this paper:

Written by Brett Berry, a woman who describes herself as a “Math evangelist who wants to convert YOU to a math person!” While I’m sure the sentiment is authentic, I am skeptical of this evangelist’s methods. Her defense of this teacher’s evaluation is rooted in the technical definition of multiplication:

\(a \times b = \underbrace{a + \cdots + a}_{b \text{ times}}\).

The problem with Berry’s apology is it’s insistence on notation over substance. To describe mathematics as learned adherence to notation is like describing the carpenter as a man who uses hammers, nails and saws, without any consideration of what he is actually building. Let’s take a look at each of her points in turn.

Notation is not mathematics

Berry’s first argument is about equality vs equivalence:

Equal is defined as, “being the same in quantity, size, degree, or value.” Whereas equivalent is defined as, “equal in value, amount, function, or meaning.”

I love precision in definitions, which is why this attempt to add precision saddens me so much. Embedding one definition within the other does not add precision in distinguishing one from the other. But let’s leave that aside and go with this argument for the moment. I’ve often found that important subtleties are only discovered by splitting hairs and seeing what happens. Let’s see how \(5 \times 3\) is equal to, but not equivalent to \(3 \times 5\).

For example, 3 bundles of 5 bananas is different from 5 bundles of 3 bananas although they total to the same number of bananas. Their structures are different.

Different how? “Equivalent” needs a context to be meaningful. Apples and oranges are (roughly) equivalent as projectiles, not so much as culinary ingredients. But the bananas in Berry’s example have no such context, other than one she artificially creates. If arithmetic is about counting (and not about notation), then the structure of the bananas is not meaningful. It is irrational to think that counting bananas would be different between three groups of five bananas and five groups of three bananas. The artificial “structure” Berry imposes on the counting, is absurd given that the apparent next lesson is the commutative property which will eradicate the meaning of these structures.

And what possible enlightenment could come from restraining the natural discovery of the commutative property? This student, exploring with pencil and paper during his quiz, has apparently discovered this wonderfully intuitive property of multiplication. And the teacher’s instinct is to squash the student’s genuine intellectual progress in order to adhere to a rigid pedagogy?

It’s common for beginners to get confused as to when it is okay to switch the order of values in binary operations.

This argument hinges on the notation being more fundamental than the concepts they represent. As if one could teach the property of addition and symbol (\(+\)) without first bringing together objects and demonstrating the concept. Perhaps this explains why the beginners get confused. Instead of explaining that \(÷\) divides numbers and \(\times\) multiplies numbers as binary operators, perhaps it would be more intuitive to explain that when I count things by multiplication, I need a way to convey that information, and the \(\times\) symbol allows for that efficient communication.

Substituting notation for understanding will inevitably fail. Understanding doesn’t come from using the “binary operators” correctly, but from having the problem “how do I convey a proportion?” and needing a notation to talk precisely about that concepts. And speaking of notation, why do we teach notation that isn’t useful? I have never met anyone over the age of 16 who uses the obelus (÷) to denote division. We don’t even have it on computer keyboard number pads. Teaching it at all is a confusing disservice when fractional notation is clearer as the symmetry of commutation is reflected. The only explanation I can see is as an educational establishment clinging to a historical dogma for nostalgic reasons.

Javascript typing is not math

Berry’s last arguments lack any grounding or even coherence as applied to teaching basic arithmetic and algebra.

It’s more important than ever for students to understand the difference between equal as a result and equivalence in meaning from a young age because it is a fundamental computer science concept.

Berry seems not to understand the computer science concept of typing.

What I do not understand is why typing would ever matter in an essay on teaching basic arithmetic

which by definition has only one type (rational numbers).

Conflating data typing with mathematical structure is so convoluted as to be incomprehensible.

It’s also a flawed analogy as the structure difference she argues with multiplication is mathematical,

and the difference in the javascript example is string vs number. Even javascript’s === operator knows there is no

difference between the summation of five threes and three fives, they are both equal and equivalent.

I encourage you to try this for yourself, Ctrl+Shift+I will bring up a javascript console in the chrome browser.

Respect the teachers?

Berry’s final arguement is entitled “The Right Mindset for Matrix Multiplication” and argues that because a matrix has a structure which restricts what it can be multiplied with, counting of whole numbers should follow a similar structure (albeit wholly artificial due to pedagogy not discovery). This argument is so baffling to me, as to render it nonsensical. This poor kid who has discovered the commutative property is to be held back and punished because 10+ years later, he may take linear algebra?

This rigid curriculum leaves no room for the creativity and discovery of real mathematics.

The nonsensical nature of the javascript and matrix math arguments reveal a dogma deeply entrenched math education. Lockhart’s Lament outlines this problem

Students are taught to view mathematics as a set of procedures, akin to religious rites, which are eternal and set in stone. The holy tablets, or “Math Books,” are handed out, and the students learn to address the church elders as “they” (as in “What do they want here? Do they want me to divide?”) … The insistence that all numbers and expressions be put into various standard forms will provide additional confusion as to the meaning of identity and equality.

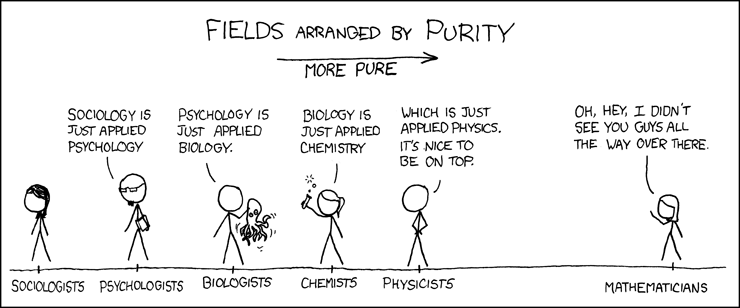

The demand for respect which comes from Berry (and her self description as an evangelist for math) reeks of this “church of math” piety and is contrary to mathematical learning as an adventure of discovery, a creative endeavor where the teacher is a midwife not a sculptor. One of the wonderful things about math is that it’s a level playing field. There are no “thou shalt”s because the math is all there is. “Does this make sense?” is the only guideline. It’s a purity not possible in most other fields which liberates the student from the burden of right and wrong to the freedom of what is possible.

Math is about creative problem solving

When I was a child, there was a patterned tile in the shower where I grew up. I remember being curious about how many tiles there were, and too lazy to even think of counting them directly. But there was a pattern in the tiles which repeated in blocks of 3 tiles by 4 tiles. And counting the blocks along one side and the other did not disturb my dedication to laziness. I remember realizing I didn’t have to count them all, I could count along one side and then the other and I could figure out how many tiles there were. This was real mathematics. No need of notation and no need of rigorous procedure. I had a problem in the world, was able to map it to an idea in my head and solve the problem. I got to invent a system, explore the intellectual toolkit inherent in all humans. This is what’s required to explore the creativity of math. I love Vi Hart’s description of math:

One of the greatest teachers I’ve encountered in my life is Paul Zeitz, who’s Problem Solving seminar course at USF taught me more about mathematics than all of the other courses I took in college combined. I’m grateful for his ability to break down the notation dogma and bring it back to understanding of the problem. “Without loss of generality let \(n=3\)” was his way of saying, let’s look at what is actually happening rather than getting lost in the quagmire of abstract notation. He encouraged that curiosity which is the root of all discovery rather than dispensing a holy message from on high.

“Mathmatics isn’t about computation, it’s about problem solving.” – Elly Schofield

Elly Schofield’s TEDx talk tells her story of being quick, accurate, and adept at strict adherence to notation, leading to success in math until the undergraduate level where she discovered the truth: that isn’t math. It’s the toolkit of math, but it’s not math. Elly describes her “personal betrayal” by the education she received as the likely reason people hate mathematics.

The strongest point from Elly’s talk is the utility of “productive failure” in practicing real mathematics. I love her idea of creating a small gap in the armor of the church of math. It doesn’t have to be an overhaul of of the whole system, but let’s make a place in math education where the kid who’s paper strayed from the rigid dogma and demonstrated real problem solving could be lauded for doing real math.

I hope that kid goes on to study real math.